How Phantom Income Happens in Real Estate

How Limited Partners Can Identify Tax Implications on Their K-1s

Investing as a limited partner (LP) in commercial real estate comes with important tax considerations. In today’s guest post, Roger Ledbetter—a CPA specializing in real estate, small business, and tax consulting—breaks down the concept of phantom income that can appear on K-1s.

Roger will walk through two examples:

In the first scenario, the deal is refinanced with a distribution paid to investors, followed by a foreclosure.

In the second scenario, there is no refinance (and no distributions), followed by a sale at a loss.

To wrap up, Roger will explain how to identify potential exposure to phantom income—especially valuable if you had an investment exit in 2024 or are evaluating a capital call in a CRE deal. On capital calls, read this:

- Leyla

The K1s that drive the most questions from limited partners in private real estate investments are when LPs are allocated income with no distribution.

While they usually spot when their address is wrong, name spelled incorrectly, and ownership percentage is off by a hundredth of a percent - they don’t always find the phantom income. And with the real estate and credit market being where it is, this is more and more likely to happen.

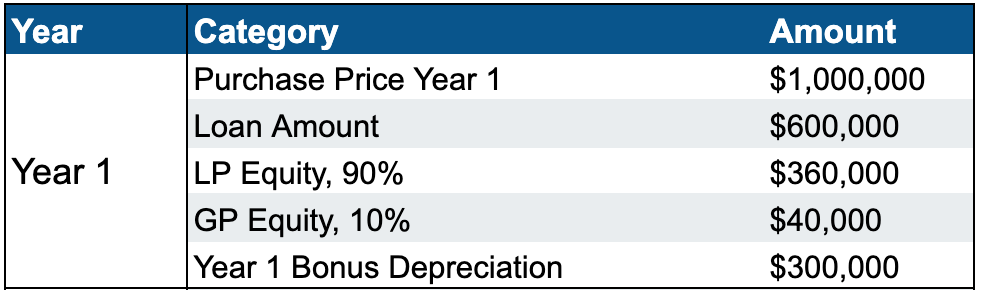

To help explain how this happens, we’ll use an example throughout this piece:

This was a very common set-up in the low interest rate environment:

GPs would raise large amounts of equity with often higher leverage than this scenario

Use the 100% bonus depreciation rules to record massive K1 losses in the first year of acquisition.

Let’s plot this out on an actual K1 to see what this would look like - assuming all LP equity was one investor.

Year 1 - Asset Purchase and Bonus Depreciation

So far so good - the LP is happy because he’s invested $360,000 and received a K1 with $270,000 in losses that can be used to offset other passive income for him.

But what most investors don’t appreciate is that the IRS treats losses on K1s equivalent to cash distributions for purposes of tracking how much basis the LP has in the investment. And that basis amount is a critical input to calculating gain on an eventual sale (or deemed sale).

But let’s fast forward on this property.

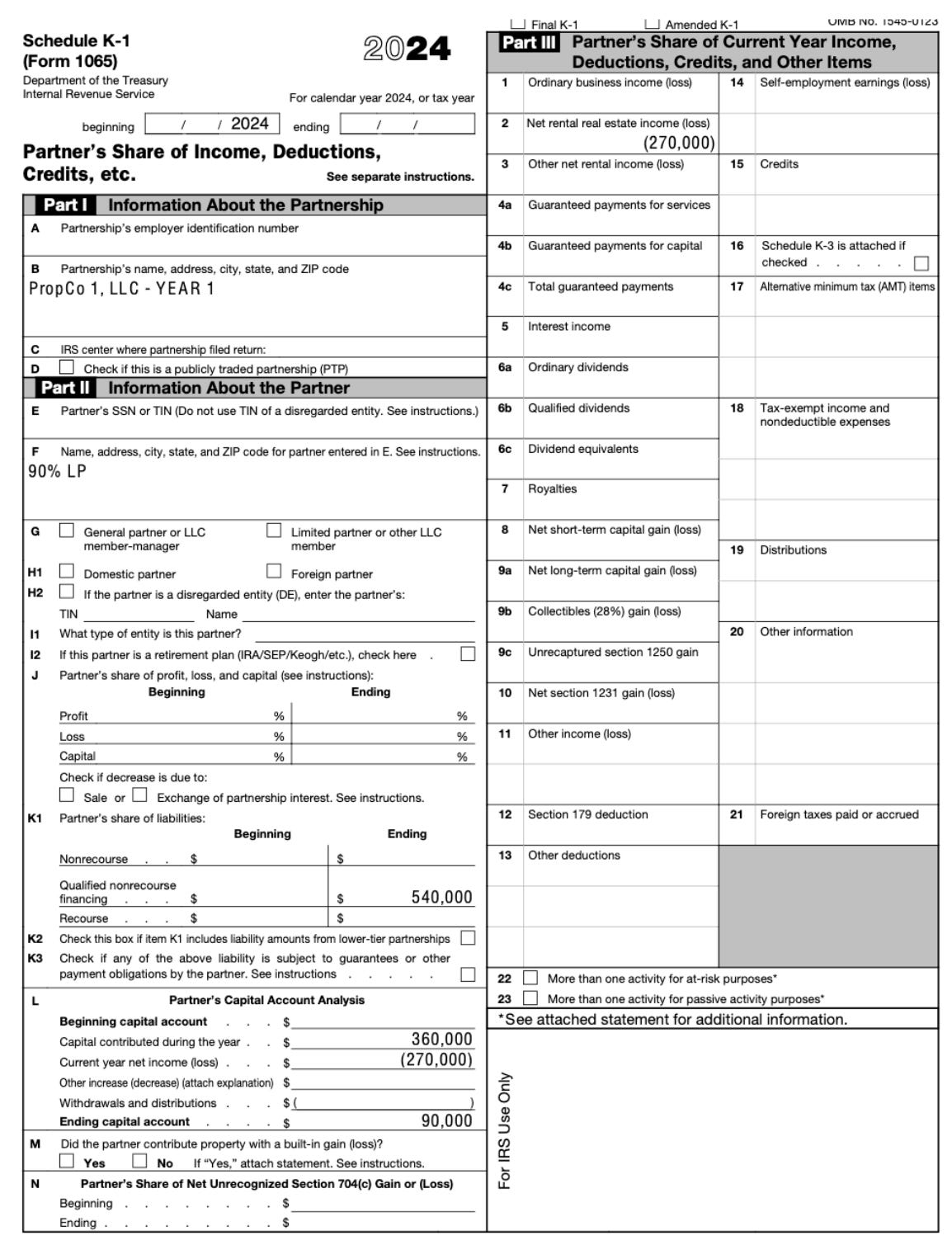

Year 3 - Refinance and Distribution

Two years after acquisition, the property has experienced substantial appreciation and the GP decides to refinance the loan and distribute the excess proceeds to the LP. (We’re going to pretend Year 2 was a wash - no distributions, just stay with me)

This was also very common and remains tax free because of a concept in partnership tax referred to as minimum gain.

What minimum gain says - in short - is that if the net book value (cost less depreciation) of an asset that secures a mortgage is less than the mortgage, the partners are deemed to have gain in the amount of that difference. It’s like “pre-gain.”

In our example, the net book value of the land and building is $700,000 ($1,000,000 purchase less $300,000 depreciation). And after the new loan the amount of the mortgage is $1,300,000 ($600,000 original + $700,000 additional). So in this example, at Year 3 there is minimum gain of $600,000 and partners can actually go “negative” in their capital account by that amount.

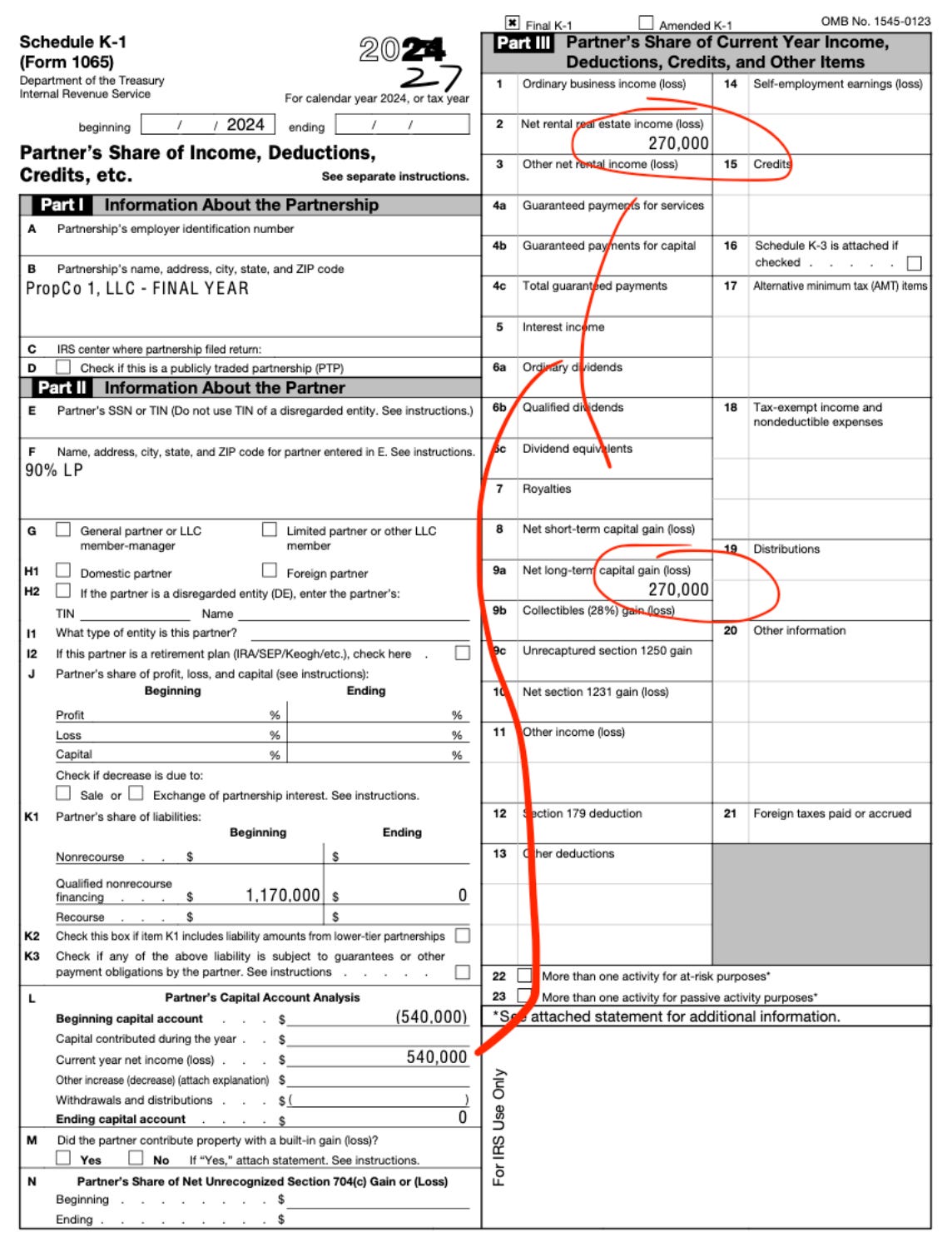

Let’s see what that K1 looks like in Year 3.

Okay, things are starting to get a little risky. That negative capital account - even though financed with legitimate minimum gain - represents future income somehow. But the LP is pretty happy because they’ve still yet to receive any income allocation and for their $360,000 investment they’ve gotten both $270,000 in losses and now $630,000 in distributions.

Leyla’s note: here’s a great case study that models an refinance mid-hold:

Year 4 - Disaster

But now things turn. The Fed begins to hike and doesn’t stop. The 10Y keeps climbing and refuses to come down long enough for a legitimate shot at refinance. The property loses value and the GP is forced into the worst spot - turning the keys over to the bank.

Losing a property to the bank and having all your LPs equity wiped out is painful - but max pain isn’t until that final K1 hits.

The tax rules treat “turning the keys over to the bank” as more than just a loss event. When the property is given up subject to a mortgage, the IRS considers the amount of the mortgage that is “forgiven” to be the sales price in a “deemed sale.” (Note these rules change when debt is recourse - but let’s continue with full non-recourse assumptions)

So the “deemed sale” results in a “real gain” as follows:

Amount of Loan “Forgiven” in Exchange for Property - $1,300,000

Basis of Land and Building - $700,000

Gain on “Deemed Sale” - $600,000

This amount of gain is further broken down into (1) recapture and (2) capital gain.

Remember Year 1, when $300,000 of bonus depreciation was taken? Well, because the “deemed sales” price of the lost property is more than the original basis, that original depreciation deduction is “recaptured” as ordinary income (mostly).

And then the amount of gain in excess of the original basis ($1,300,000 deemed sales price - $1,000,000 original basis = $300,000) is capital gain.

Phew - okay let’s see what this last K1 looks like:

This is the year the LPs will have questions. And they will usually sound like this:

“I invested $360,000 and only received $630,000. That is only $270,000 of cash over my original investment. My CPA says there is a mistake and you are double taxing me. This needs to be fixed ASAP. Thx”

However, they forget that Year 1 of depreciation that must be paid back. And with this additional capital gain they may be in a higher tax bracket than when they received the original losses - causing extra pain.

Year 4 Scenario 2 - No Refinance, Just Pain

An additional wrinkle I’ve seen is when there were never any distributions. Instead, additional debt is taken on to operate the failing property and LPs are allocated incremental losses - driving down their capital account. And when the distressed property is finally given up, they have gain for which they never received $1 of distributions.

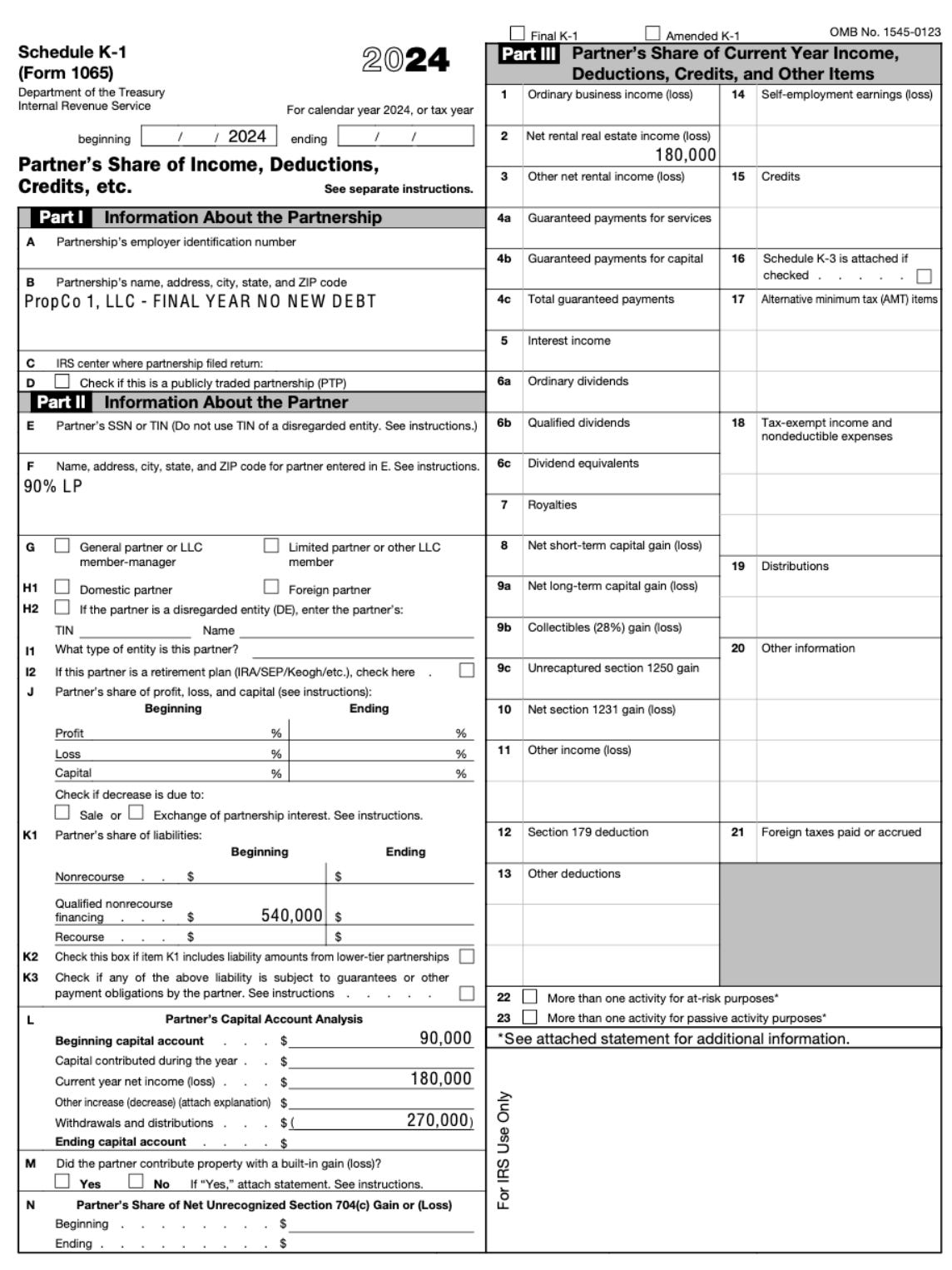

So in our above example, let’s say that immediately after Year 1, the property is sold for $900,000 - no additional debt was taken out or distributed. There would still be recapture gain for the difference in the sales price ($900,000) and basis ($700,000).

This gain would be full recapture (ordinary rates).

This doesn’t sound so bad between two tax years - but when a property has been held for 5+ years, all depreciation has been squeezed out early and no distributions taken, it can be an absolute gut punch.

Here is what that final K1 would look like if sold in Year 2 without any new debt:

Note that in this scenario, if the property was actually sold then the LP would (hopefully) get their investment back which is reflected in the $270,000. But remember if for some reason they didn’t get that back, it would be a capital loss on their personal tax return while the recapture is still ordinary income.

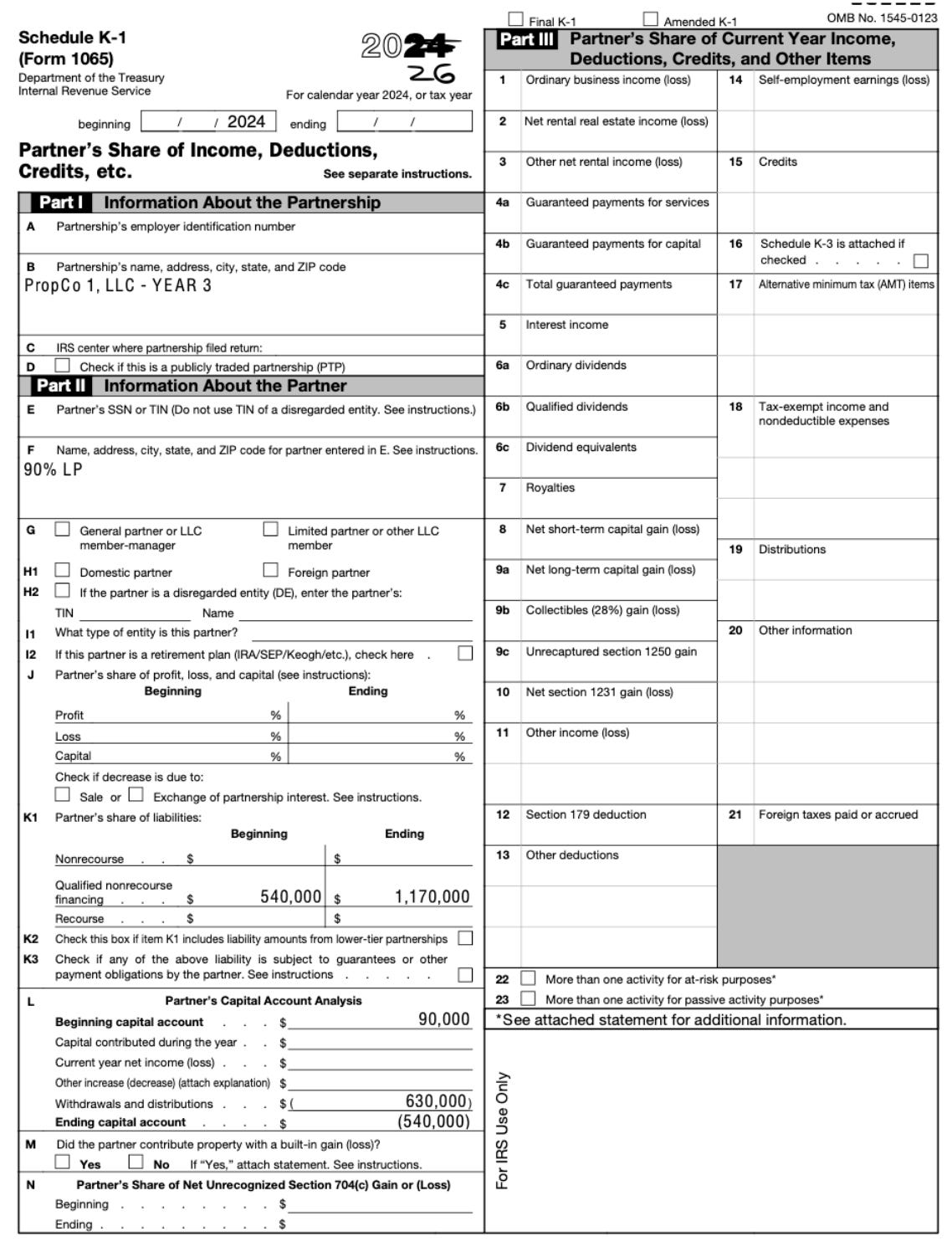

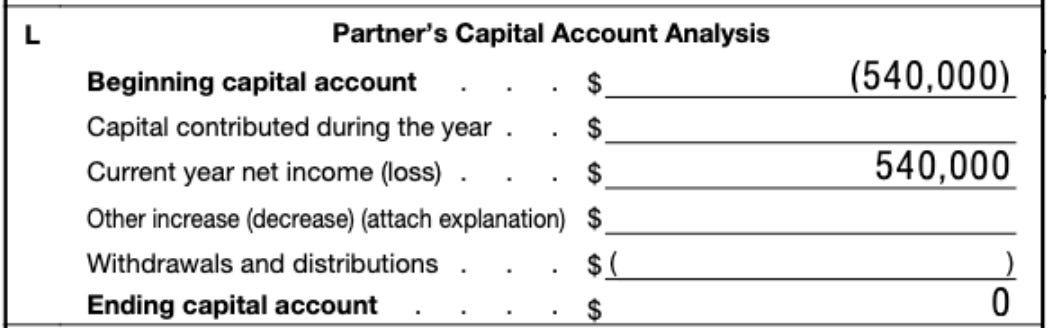

How to Spot the Exposure?

Last bit - how can you tell if you are susceptible to phantom income? Easiest way is to look at your K1. The Partner’s Capital Account Analysis box is a great tracker of your tax basis. If that is negative because of debt - you have exposure. In our example, the $540,000 of negative capital - even though it was through minimum gain - represented the amount of possible phantom income:

Caveat - I’m a tax advisor, but probably not your tax advisor. These concepts were covered at a high level for informational purposes only. There is additional nuance that should be considered before making any decisions or panicking in any sort of way. As always, consult your tax professional.

About the Author:

Roger Ledbetter has been a CPA in Texas for nearly twenty years. He is currently the managing partner of Baldridge Financial, a tax and accounting firm based out of Houston, Texas that specializes in real estate, small business, and tax consulting and planning. Prior to joining Baldridge Financial, Roger was a tax partner and Houston market CRE leader for Baker Tilly, a top-10 accounting firm.

Roger is active on X / Twitter, writes a weekly tax and accounting newsletter, hosts a weekly podcast (Today in Tax Court), and is raising 4 young children with his incredible wife.

If you’d like to connect separately, please feel free to send an email to roger@baldridgecpa.com or connect with him on X / Twitter.

Thank you. This is most helpful. I am facing a capital call now due to refinancing at higher interest rates. Would it be practical to ask the GP to project an estimated K-1 after the capital call and refinance? TIA