“It takes 20 years to build a reputation and five minutes to ruin it.” - Warren Buffett

A few months ago, I reviewed a pitch deck for a multifamily deal. The deck was light on details, but I went through the business plan and the limited information provided. The deal was presented as a new acquisition—complete with a purchase price, new loan financing, and standard fees (including an acquisition fee, of course).

But something was nagging at me.

I checked county records, and sure enough, the same sponsor had purchased this property years ago. This wasn’t a new acquisition—it was a recapitalization disguised as one.

‼️ To be clear, there’s nothing inherently wrong with recapitalizations. GPs have plenty of legitimate reasons to recap a deal. But investors deserve full transparency. Recapitalizations should be disclosed—clearly and explicitly.

Which brings us to today’s case study. (At the end of the article I’ll show you how to look this information up yourself).

Before we dive in:

Accredited Insight is a unique newsletter: we are the only voice offering a perspective from the LP seat. We cover what we see and what we learned in private markets—drawing on insights from hundreds of deals and numerous conversations with sponsors, LPs, and service providers.

By becoming a paid subscriber, you will gain access to our database of over 30 case studies and articles on everything you need to know to become a better investor. If you are a GP, this is your window into the world of capital allocators. Click the button below and chose your preferred term:

Deal or No Deal?

Just a friendly reminder: this is for educational purposes only, not financial advice. Names, numbers, and details have been tweaked to keep the sponsor’s identity confidential.

Deal Summary

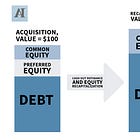

The offering memorandum claimed the property was being acquired at a discount (on a cost-per-square-foot basis) compared to similar properties. The business plan called for $20K per unit in renovations. That’s as far as details went. Projected hold period: 5 years.

Let’s break this down.

1. No Pro Forma 📊

The deck didn’t include a detailed pro forma, so we had no way of verifying the expected rent premium. Here’s why that matters:

Let’s assume the GP spends $20K per unit on renovations and increases rent by $100/month. That’s a 6% return on investment ($100 × 12 ÷ $20,000 = 6%).

That’s a terrible use of capital. Why? Because investors could earn over 4% in risk-free Treasury bills. Why take on real estate risk for a marginal increase in returns?

2. The True Cost of Fees 💸

Fees and costs accounted for 22% of the "purchase price"—before selling costs (which would add at least another 3%). That means the property must appreciate by 25% just for investors to break even.

❗️The key question in any value-add deal:

Will these renovations actually increase the property’s value?

The answer isn’t as straightforward as you’d think. Since property value at sale is driven by net operating income (NOI), we need to know how much rents will actually increase. And without a detailed pro forma, that’s impossible to assess.

3. 🐘 The Elephant in the Room: Recapitalization

This property happens to be in a disclosure state, meaning public records revealed the prior sale. That’s not always the case—some states (I’m looking at you, TX) don’t disclose sale prices. However, even in Texas, you can check deeds to see outstanding loan amounts.

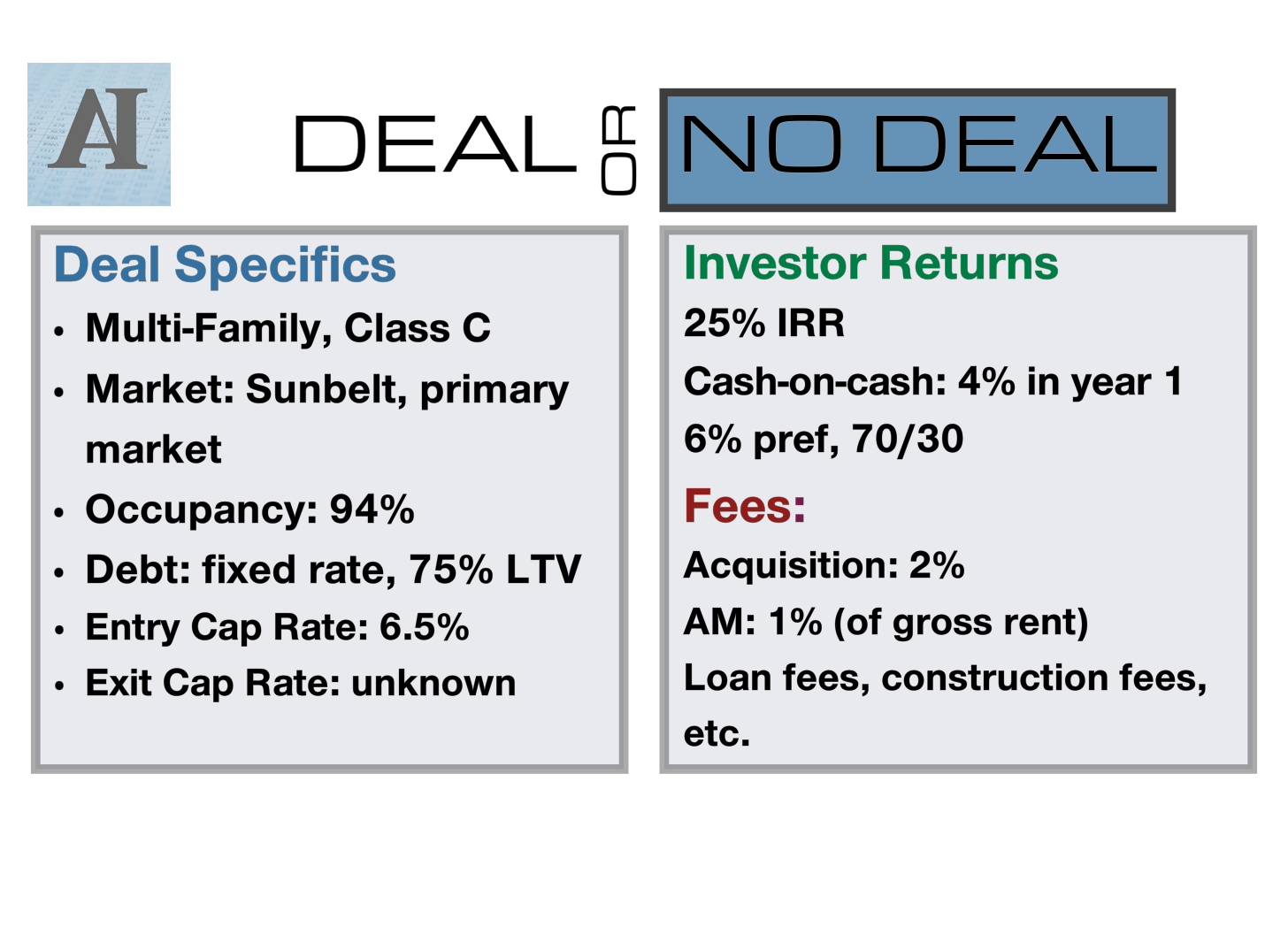

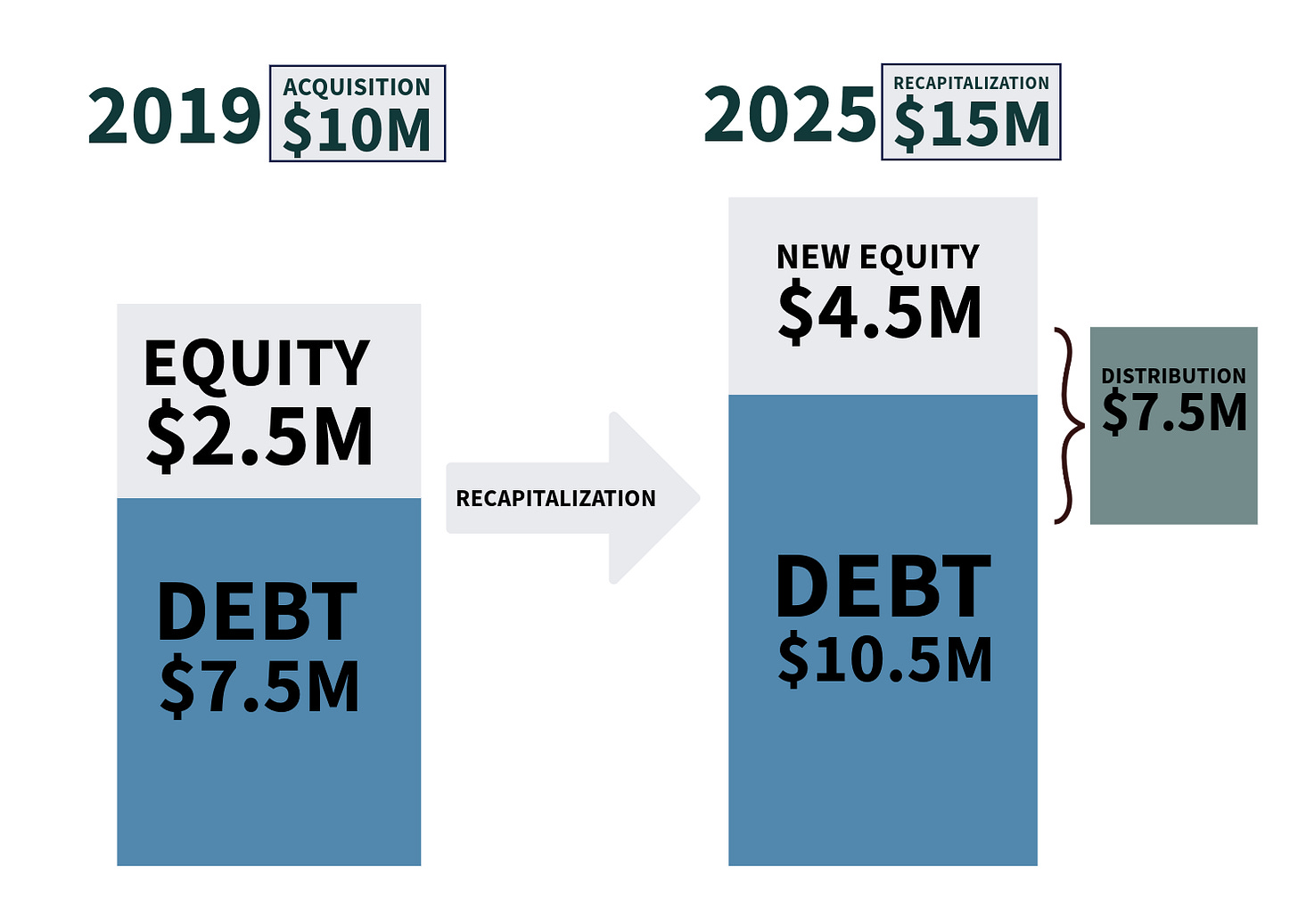

Now, let’s walk through the numbers. I’m making several assumptions here: I know prior purchase price and loan amount, but I don’t know how much equity was raised. Don’t hold my feet to the fire: the goal here isn’t to pinpoint the exact returns for the original equity holders but to illustrate how the new equity is being used.

2019: The sponsor raised $2.5M in equity and secured a $7.5M loan.

2025: The sponsor refinanced with a $10.5M loan (paying off the old $7.5M loan and receiving $3M in new funds). They also raised $4.5M in new equity.

Total new cash: $7.5M

Where does it go?

The sponsor returns old equity (plus preferred returns and promote).

The remaining cash is the sponsor’s carry.

And the “new” LPs? They’re investing in a deal where the sponsor has virtually no skin in the game—but still earns their carry and fees.

❓Is this illegal? No.

But it creates a serious misalignment between the new LPs and the GP. The sponsor is cashing out while new investors are coming in with fresh capital—without fully understanding the deal’s history.

📌 How to Look Up Public Records

Want to verify a deal’s history yourself?Here’s a resource that can help:

To look up property deeds in assessor records, start by visiting the website of the county assessor or recorder's office where the property is located.

Hint 🤫: this is a great way to spot-check hard money funds.

Many counties offer online search portals, allowing you to search by owner name, address, or parcel number. Deeds typically list sale dates, loan amounts, and property transfers, which can help uncover past transactions.

➡️ In non-disclosure states (like Texas), exact sale prices may not be available, but you can still check deed records to see mortgage amounts, which provide clues about financing and recapitalization.

Thank you for reading! Have a wonderful week - and subscribe, if you haven’t yet: next week, we’ll publish a deep dive into what needs to be included in a pitch deck.

Thanks for the interesting case and context, Leyla. I find the notion of being an LP in a class C deal almost repulsive. Too many uncertainties about surprise maintenance costs and problems to be encountered in renovations. Something pushing Class B up a notch or two would seem less fraught with unknowns.

great insights on all the hidden items